Advancing Health Equity with Multilevel Interventions

In a world where the zip code you are born in can predict your life expectancy, it’s clear that health inequities are not just about biology; they’re about the social conditions surrounding us. Despite decades of research, the United States continues to struggle with some of the worst health outcomes among high-income countries, much of which can be attributed to the harmful social determinants of health (SDOH). These determinants, such as access to quality housing, income, and the presence of structural racism, have a profound impact on the health of millions of Americans.

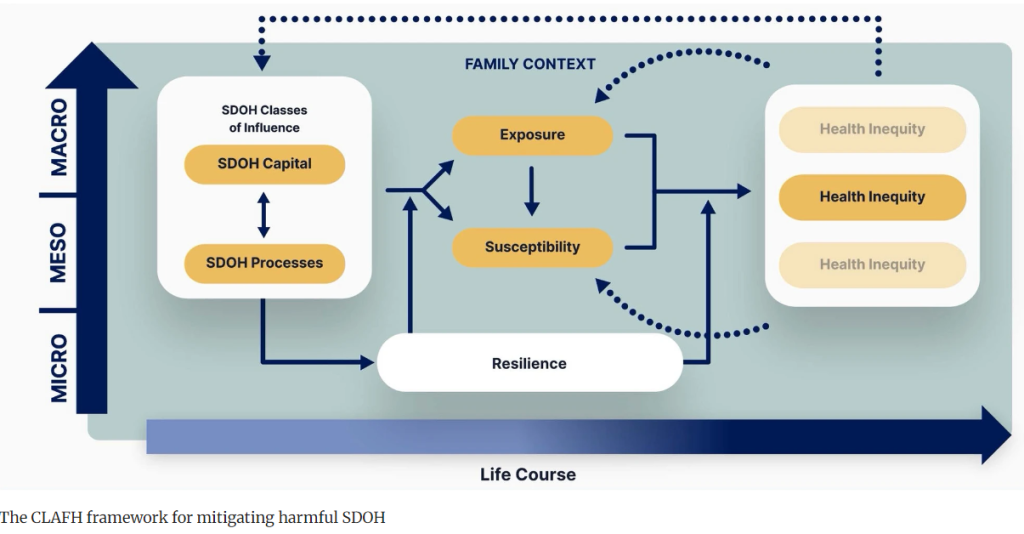

Recent research introduced a groundbreaking framework that offers a new way of tackling these inequities. The framework, developed by the Center for Latino Adolescent and Family Health (CLAFH), provides a roadmap for designing and evaluating interventions that address these harmful social processes. What makes this framework special? It’s designed to help researchers and public health practitioners develop multilevel interventions that target the core mechanisms driving health inequities, allowing for more effective and sustainable health outcomes.

Why Multilevel Interventions?

Multilevel interventions work on different levels of society—from individuals and families to institutions and broader systems—making them well-suited to address complex, layered problems like health inequities. The CLAFH framework helps researchers identify how factors like racism, poverty, and housing interact and affect health. By understanding these dynamics, public health professionals can design interventions that target not just one aspect of the problem but address it holistically.

Take the ongoing evaluation of the Nurse-Community-Family Partnership (NCFP) intervention, for example. This nurse-led initiative leverages the CLAFH framework to tackle COVID-19 disparities in one of the most affected areas of the United States: the South Bronx, New York. The NCFP focuses on improving COVID-19 testing and vaccination rates, along with building mutual aid networks that support families during the pandemic.

The Four Steps to Better Interventions

The CLAFH framework lays out a four-step process for designing effective interventions. These steps are designed to help practitioners and researchers get a full picture of the issues they’re addressing, from community health inequities to the individual factors at play.

1. Identifying the Health Inequity and Context

Before creating an intervention, the framework asks researchers to identify the specific health inequity they want to address and the community context in which it exists. This step is crucial to ensure that the intervention is tailored to the community’s needs. In the case of the NCFP, the inequity in focus was the disproportionately high rate of COVID-19 infections and deaths in the South Bronx, a low-income, predominantly Latino, and Black neighborhood. This first step emphasizes community engagement, ensuring that local voices are part of shaping the solution.

2. Operationalizing the Framework

After identifying the inequity, researchers proceed to define the specific contributing factors. For instance, in the South Bronx, overcrowded housing and lack of access to healthcare were major drivers of COVID-19 transmission. But the framework goes deeper—it also identifies broader social factors like the historical underinvestment in minority communities and the lack of trust between residents and the healthcare system.

Side note: I read a really great book for a project last year called The Color of Money. It focuses on how economic policies, specifically banking, perpetuate inequities in minority communities. It’s worth checking out!

3. Designing the Intervention

After understanding the root causes of the inequity, the next step is designing an intervention that addresses these factors on multiple levels. The NCFP intervention, for example, didn’t just focus on getting people tested for COVID-19. It also provided families with customized infection control plans, established trust with community members via nurses and community health workers, and tackled systemic issues by improving healthcare accessibility at home.

4. Evaluating the Intervention

The framework finally details how to assess the success of the intervention. For the NCFP, this involves measuring individual-level outcomes, such as testing and vaccination rates, as well as household-level outcomes, like how effectively families implemented infection control measures. This comprehensive evaluation method ensures a full grasp of the intervention’s impact and enables ongoing improvements to enhance its effectiveness in the long run.

The Power of a Holistic Approach

“CLAFH framework is powerful because it goes beyond traditional public health approaches that focus solely on individual behavior change. Instead, it recognizes that health inequities are influenced by broader societal forces such as racism, classism, and discrimination, which interact at the individual, family, and community levels.”

For example, consider a community where many residents lack health insurance. A typical public health intervention might focus on encouraging people to go to the doctor more regularly. But without addressing the underlying issue—lack of access to affordable healthcare—such efforts are unlikely to make a lasting impact.

The CLAFH framework provides a way to address these bigger problems by considering multiple levels of influence. In communities like the South Bronx, this means not only encouraging COVID-19 testing but also making sure that families have the resources and trust they need to follow through on public health recommendations. It means addressing the systemic racism that has led to underinvestment in healthcare in the first place.

Real-World Application: The NCFP in the South Bronx

The NCFP intervention shows how the CLAFH framework can work in real-world settings. The South Bronx, like many low-income communities of color, faced significantly higher COVID-19 death rates compared to the rest of the country. To address this inequity, the NCFP intervention used a nurse-led, family-centered approach that tackled multiple levels of the problem.

By focusing on individual behaviors—like increasing testing and vaccination uptake—alongside household-level interventions—such as family infection control plans—the NCFP was able to address both immediate and long-term health concerns. At the same time, the program worked with community organizations to build trust and improve access to healthcare, tackling the broader social determinants that contributed to the area’s vulnerability.

Join the Conversation

What do you think? Could a multilevel intervention approach be used to tackle other public health crises, like diabetes or heart disease? How might this framework be adapted to your community’s unique challenges? Share your thoughts in the comments below or on social media using #MultilevelInterventions.

Join the Community – Get Your Weekly Public Health Update!

Be a health leader! Subscribe for free and share this blog to shape the future of public health together. If you liked this blog, please share it! Your referrals help This Week in Public Health reach new readers.But without addressing the underlying issue—lack of access to affordable healthcare—such efforts are unlikely to make a lasting impact.