Combating COVID Misinformation – the WHO and HOW.

Over the past week, a few pieces of information have been stuck in my head. The first is that nearly 99% of all COVID deaths in the United States are occurring in the unvaccinated. To put it bluntly, this is bonkers. We have an evidence-based, cost-effective, widely accessible method to prevent death by COVID. People are choosing not to use it.

The second item is that the politicization of health-related information continues to intertwine with other culture bugaboos like critical race theory. This is impacting policy-making on a local level, where a lot of meaningful change happens. Here’s what happened at my local school board, of which I will not be a member this fall. The charged atmosphere is making it extremely hard to implement public health interventions through standard methods.

The third item was this Twitter thread from Nicholas Grossman at the University of Illinois. Click below to go through the whole thread. It’s really worth your time.

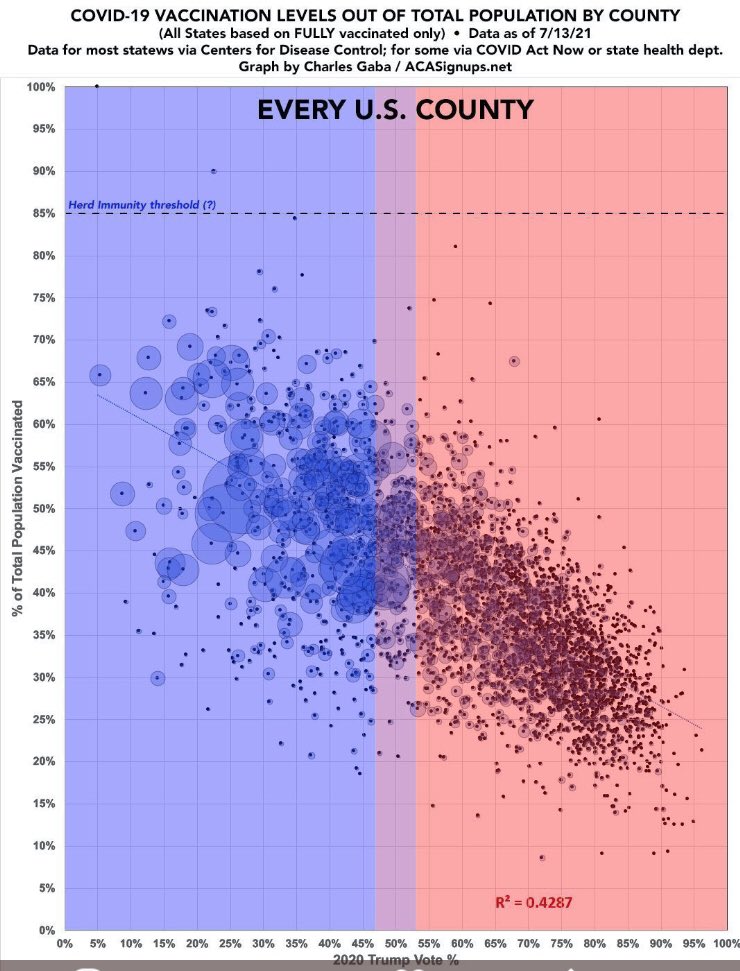

Grossman notes that the vaccine-hesitant are not a monolithic group, and should not be treated as such. He identifies three categories: 1) the ideological anti-vaxxers, 2) the hesitant (so the young and/or cautious), and 3) the political statement people (which he cited in the below graph).

He argues that the first and third categories are potentially unreachable. The anti-vaxxers have had years of evidence noting the large benefits and low risk of public vaccinations strategies and have not been swayed. The political statement people have dug in, and we know that people will double-down on their beliefs rather than update them. Therefore, in order to be maximally effective, public health efforts should be focused on category two: people on the fence.

Even in health facilities like hospitals and nursing homes, there are still laggards who have chosen not to vaccinate. In light of such an apparently big cost-benefit ratio (prevention vs. minimal effort), we have to ask why?

The Surgeon General sez…

Much of this phenomenon is driven by misinformation. Vivek Murthy, the surgeon general, points out a few reasons why misinformation spreads. (You can download the short report at this link)

- The highly charged and emotional nature of the material. When our anxiety and emotions are up, we’re more likely to react strongly to something. With the highly charged sociopolitical climate in America, this can lead to an accelerated spread of such content. This is driven by:

- Spread by Social Media algorithms that prioritize high engagements. If there a particular post or piece of content that leads to commenting/liking, it is more likely to show up higher in a social media feed. So, there’s a positive feedback loop here whereby emotional content get promoting more heavily so more people read/react/comment.

This is a good place to point out the cover image of this article (the women in the bikini) is an experiment by me to see if it leads to more engagement. Sure, it has nothing to do with the title, but does did it arouse attention? And did it promote clicks on this article?

What’s the solution to this?

The surgeon general breaks down actions that different community stakeholders can take.

Individuals and families can learn how to identify accurate health information and engage loved ones in conversation around health misinformation problems. And yes, this is really tough. In many cases, it’s easier to just ignore the relative or friend who is spouting misinformation. And this goes back to the challenges laid out by Grossman. Are the values and views held by individuals ideological, political, or reluctance-based? When I was a clinician, I found it much easier to work with reluctance than the other two. I fully admit to just muting or unfriending/unfollowing people who spread misinformation rather than engaging them. We’ve all seen the circular arguments that happen on social media.

And yet, social pressure is a key way of shaping and communicating influence. So, while we might need to focus on the reluctance category, we can still work to communicate our own values broadly if they are science and public-health-based.

Educators can focus on health literacy and help to build up resilience to misinformation. As educators and school boards are finding out all around the US, this is a similarly heavy lift. While school boards have a fundamental mission of promoting quality public education, there are other stakeholders who get a say in how educational policy is selected and implemented. Teachers, parents, and the community at large all have a vested interest in the local school system. The cultural aspects here make it extremely tough to focus on generational changes to educational content without running into a lot of backlash, as my fellow candidates are finding out.

However, information synthesis and media literacy are key 21st-century skills. In order to be responsible stewards of community growth, we must provide the knowledge and skills to comb through and vet different sources of information to arrive at informed conclusions.

Health Care Professionals can proactively engage with patients to empathetically listen, process concerns, and provide accurate information. I recently saw a video from Atul Gawade where he talks about how bedside manner is also a medical intervention: one that has to be taught, refined and mastered.

Journalists can endeavor to provide accurate, fact-checked information that provides proper weight to the credibility of sources. Just because there are multiple sides to an issue doesn’t mean those sides have equal evidence and support behind them!

And yes, journalists and the media landscape in general are driven by mission AND sales. The most shocking, titillating and emotionally arousing stories are the ones that gather the most attention. They also yield the most revenue. This is not new. One of the best movies I watched this year, Nightcrawler, covers this very topic. So, is there a way to make scientific information more exciting, more engaging, and more sexy? Surely, it’s not just bikini photos?

Tech Platforms can do a lot more, but it’s not worth getting into here. But let’s take a quick detour into PubTrawlr. We are trying to provide the best possible, synthesized overview of the literature. Like everyone, though, our algorithms are a work in progress and are always improving. We want to provide an appropriate weighting of quality sources.

Researchers can continue to study how we consume and process information. There are volumes and volumes written about this topic. What is potentially less clear is how these findings get used in dissemination efforts. Enter implementation science (and to be honest, marketing).

Putting it all together

It’s clear that combating misinformation requires a multi-leveled, multi-method approach. It’s also not a change that will happen quickly. Large-scale, public health changes have to start with small incremental changes. However, it’s also true that you, as an individual, can take it upon yourself to do some small part in putting scientifically valid information out there. It’s tough, but worth it.

How do you access research?

We here at PubTrawlr want to know how people access and use scientific information. Take the below survey to let us know. In exchange, we’ve got some cool swag for you. The survey closes on Monday!

[wpcdt-countdown id=”774″]

What’s the problem?

There are tons of great ideas out there. But these don’t get used. What are the ways that people consume scientific information?