Inside the Hidden Architecture of Health Misinformation

When a cholera outbreak hit a coastal city last year, nurse Laila A. found herself battling two epidemics at once—disease and disinformation. As she rushed between patients, she fielded messages from neighbors claiming vaccines were tainted and that hospitals were hiding deaths. The official hotline had accurate information, but no one trusted it.

“People weren’t ignoring science,” she said. “They were drowning in noise.”

Her story illustrates what the World Health Organization calls the information environment—the complex web of media, technology, and human behavior that shapes what people believe and how they act on health guidance

Why Information Environments Matter

The WHO-commissioned review, led by Becky White and colleagues, pulls together research from 22 studies and operational reports across sectors—from humanitarian aid to digital security. Its central argument is striking: information access itself is now a social determinant of health. Just as housing or education can predict well-being, so can the quality and equity of our information systems.

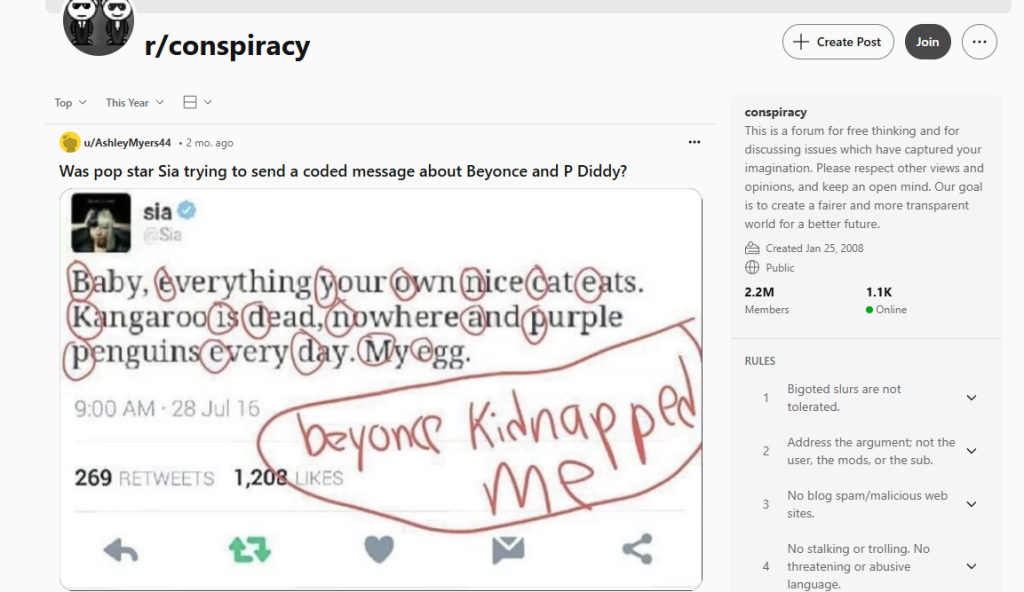

During the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people faced a parallel crisis—too much information, too little clarity. This “infodemic,” as WHO terms it, overwhelmed public health messaging and fueled distrust.

The new review asks a simple but urgent question: How do we measure and improve the environments in which people make health decisions?

What the Review Found

White et al. mapped dozens of frameworks—some academic, some field-tested—to see how they assess information flow, quality, and trust. They found no universal model, but several promising approaches:

- Comprehensive, systems-based tools – Internews and the CDAC Network have conducted community-level “information ecosystem” assessments in Syria, Türkiye, and California, combining interviews, media analysis, and trust mapping.

- Sector-specific scans – USAID’s Digital Ecosystem Country Assessments evaluate connectivity, literacy, and governance, which are useful for understanding how digital divides shape health communication.

- Community-driven frameworks – Projects like El Tímpano in California and Estrada et al.’s rural Latino studies used participatory mapping to reveal how residents share health information through churches, Facebook groups, and informal networks.

- Emerging national initiatives – Canada’s Digital Media Research Network now issues monthly “Information Ecosystem Situation Reports” to track polarization and misinformation trends

Across these efforts, the domains most often measured included:

- Information needs and access

- Production and flow of information

- Quality and reach of messages

- Trust in institutions and messengers

- Digital literacy and infrastructure

Key Insight

“Assessing an information environment is a critical step in identifying barriers and facilitators that impact different populations.”

From Theory to Practice

Public health professionals often focus on content: clearer campaigns, better data visualization, stronger messengers. This review argues that those tactics fail if the environment is polluted—when algorithms reward outrage, local radio lacks resources, or communities distrust authorities.

A practical takeaway: before designing new health messages, agencies should audit the information landscape they’re entering.

That means asking:

- Where do different groups actually get health information?

- Which channels carry credibility—and which spread confusion?

- What systemic barriers (language, cost, censorship) distort access?

These assessments don’t need to start from scratch. The WHO and partners are developing modular tools that combine desk research, digital analytics, and participatory mapping, adaptable from national ministries to local NGOs.

What This Means in Practice

For local health departments and community partners:

- Conduct quick “information scans.” Use short surveys or focus groups to identify trusted messengers and misinformation hot spots.

- Integrate communication audits into emergency preparedness plans alongside surveillance and logistics.

- Train CHWs and clinicians to recognize information inequities as health inequities—just as serious as access to care.

- Collaborate with journalists and digital researchers to monitor rumor patterns and audience sentiment.

- Invest in trust infrastructure. Transparency, multilingual materials, and local partnerships build resilience long before the next crisis.

Barriers and Next Steps

The review highlights three major obstacles:

- Conceptual confusion. Terms like information environment, ecosystem, and landscape are used interchangeably, making comparisons difficult.

- Data fragmentation. Some tools capture social media trends, others map community networks—but few integrate both.

- The research–practice gap. NGOs innovate rapidly in the field, while academic models lag behind peer-review timelines.

Bridging these gaps will require joint frameworks, co-authored by practitioners and researchers, that can evolve as technology and society change.

White et al. call for “robust models that remain agile” — capable of adapting to new platforms, political climates, and cultural contexts

Why It Matters Now

In 2025, misinformation is not just a communication problem; it’s a public health determinant.

From vaccine hesitancy to climate denial, information failures ripple into policy paralysis and preventable deaths.

By treating information environments as infrastructure—something to maintain, monitor, and repair—health agencies can protect communities before crises hit.

Or as nurse Laila put it: “You can’t fight rumors with silence. You have to understand where they grow.”

Conversation Starters

- How might your agency measure the “health” of its local information environment?

- What existing community networks could help track or counter misinformation?

- If information is a social determinant of health, how should that reshape funding and workforce priorities?