Destined to Suffer. How Prosperity Theology Is Shaping U.S. Health Policy

What if your health wasn’t just a matter of biology or economics, but of divine judgment?

For centuries, American culture has been shaped by an unspoken theology: that the healthy are favored, and the sick are suspect.

Today, as proposed cuts to Medicaid target the most vulnerable, it is worth asking. Are we still living under the shadow of predestination?

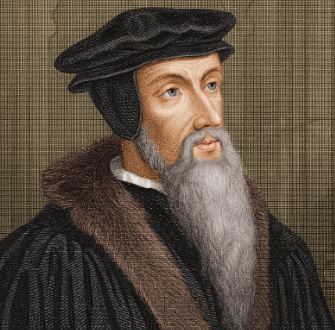

Calvinism and the American Ethos of Predestination

From the very beginning, Calvinist theology has been a core part of the American experience. Early American settlers, especially the Pilgrims and Puritans of New England, were steadfast Calvinists who believed they were a “chosen” people on a divine mission in the New World.

These settlers believed in the doctrine of predestination, the idea that God had preordained salvation for a select few. In their view, worldly success or failure could be seen as a sign of God’s favor or disfavor. Hard work, thrift, and personal responsibility were not just virtues but rules in this new society.

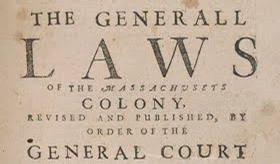

In fact, the Puritans made the Protestant work ethic a law. A 1648 Massachusetts statute threatened punishment for anyone who “spend[s] his time idlely or unprofitably.” The message was clear: God helps those who help themselves, and idleness was not just an economic issue but a sin.

It is therefore ordered and by this Court declared, that if any person be found an idle and unprofitable liver, not giving due attendance to some honest calling, and have not estate to maintain himself, or shall misspend his time and neglect his calling, whereby he becomes burthensome to the place where he lives, or to others, every such person shall be sent to the House of Correction, there to be kept at work, and be punished according to the nature of his offence.

This Calvinist influence created a culture that saw no need for a broad social safety net, as providence was believed to reward the diligent. As one historian notes, the early Americans believed “there was no need for a social safety net: there was God.” If one worked hard, God would provide; “a benevolent God…would reward virtue with worldly success”.

Conversely, poverty or misfortune might be seen as a form of divine judgment or personal failure. The idea that “we are masters of our own destiny” became ingrained in American culture. If you didn’t reach success or well-being, the logic was, “you either didn’t work hard enough, you didn’t deserve it, or it wasn’t meant to be yours.”

In other words, those who struggled were often seen as responsible for their fate – a reflection of the Calvinist-influenced idea that outcomes in life are predestined or earned by one’s character.

The Prosperity Gospel: Faith as the Path to Health and Wealth

Fast-forward a few centuries, and the Calvinist idea that some people are destined for salvation and others for damnation has reappeared in a very different theological form: the prosperity gospel. Promoted by televangelists, megachurch pastors, and influencers, this modern movement makes a bold claim: if you have enough faith, God will bless you with money, good health, happy relationships, and personal success. According to this view, spiritual belief becomes a transaction. Faith in, miracles out.

At first glance, prosperity theology and Calvinism appear to be very different. Classical Calvinism emphasized God’s total sovereignty: salvation and suffering were predetermined, completely outside human control. The prosperity gospel, on the other hand, focuses heavily on human effort, especially the believer’s faith, positive thinking, and willingness to “claim” their blessings. While Calvinists believed that no effort could change their fate, prosperity preachers teach that anyone can succeed if they just believe hard enough.

However, beneath these theological differences, a deeper cultural continuity exists. Both traditions share a core belief: that material success and good health indicate divine favor, while misfortune suggests a spiritual shortcoming. Calvinists interpret worldly outcomes as signs of one’s eternal election. Prosperity gospel followers view them as evidence of faith, or its lack.

This is why prosperity theology resonates so deeply in American culture. It provides a comforting, if oversimplified, answer to life’s inequalities: those who succeed must be doing something right. If you’re wealthy or doing well, it is because God is pleased with you. If you’re struggling, the logic goes: you must be doing something wrong, whether spiritually, morally, or behaviorally.

As one writer describes it, the prosperity gospel “attributes misfortune to something that can and should be kept at bay through faith and prayer.” The real danger, however, is in its flip side. It turns suffering into a moral failing. Health and wealth are moralized, while illness and poverty are viewed suspiciously. it is not just about someone being unlucky; it is about them not believing hard enough or not deserving better.

Even many Americans who reject overt prosperity preaching still adopt this mindset. There’s a persistent cultural belief that people “get what they deserve.” Success is earned, and failure often reflects poor choices or weak character. Sociologists have shown that Americans are much more likely than people in other countries to downplay the role of chance, luck, or structural forces in determining life outcomes. This belief is a lingering shadow of Calvinism, reflected through the modern glow of prosperity theology.

The Legacy of “God Helps Those Who Help Themselves”

The lasting influence of Calvinism in the U.S. is evident in our mixed feelings about social welfare. The old Puritan ethic of self-reliance and hard work has created what one author calls an American “aversion to providing help to those in need.” If everyone supposedly has the chance to succeed through effort, helping the poor can be viewed as coddling the lazy.

The saying “God helps those who help themselves” (often wrongly attributed to scripture) clearly sums up this view. In the past, this idea was so influential that colonial leaders believed any form of “handout” would weaken divine justice and undermine personal effort. In the 17th-century Puritan view, God was fair and gave people what they earned, so helping others might even seem to go against the natural moral order.

It’s like people were distributed copies of the Bible that omitted the Beatitudes.

Over time, this attitude secularized into the famed “self-made man” narrative of the American Dream. It celebrates individual effort and suggests that outcomes (wealth, health, success) are mostly the result of personal choices. Indeed, the idea that “outcomes in life are the direct result of our actions” has “festered in the United States for centuries”. This cultural story leaves little room for systemic factors or sheer bad luck.

Believing people “get what they deserve” makes it easier to accept vast inequalities; it leads us to subconsciously assume that disadvantaged groups must be inferior or have done something wrong. Random illness or misfortune becomes an uncomfortable anomaly to be explained away or ignored.

The Quakers and Morality

Importantly, not all Americans have embraced such a harsh outlook. There is an equally real and powerful tradition of compassion, communal duty, and egalitarianism in American life, often rooted in religious values that stood in direct contrast to Calvinist predestination. One of the clearest expressions of this counter-tradition came from the Quakers, also known as the Religious Society of Friends, who emerged in colonial America as a spiritual and moral force committed to equality and mercy.

Unlike the Calvinists, who believed that God had predestined a select few for salvation and that worldly success was a sign of divine favor, the Quakers emphasized the “inner light”, a belief that God’s presence exists in every person, regardless of wealth, health, or social status. This belief in universal spiritual dignity led them to reject moral hierarchies and view suffering not as a reflection of sin or divine disapproval, but as an inherent part of the shared human condition.

In practice, this theology translated into radical compassion. Quakers were early leaders in prison reform, mental health care, and the creation of free hospitals. In Pennsylvania (and Philly), where Quaker influence was especially strong, they advocated for humane treatment of the sick and poor and opposed punitive approaches to poverty. Rather than blaming people for their misfortune, they asked how society could alleviate it. Their actions were rooted not in a desire to reward the “deserving,” but in a deep sense of moral obligation to care for all.

This ethos viewed illness and misfortune as opportunities for solidarity, not scorn. Quakers were among the first religious groups to recognize that health and well-being were communal responsibilities and that public support systems reflected spiritual maturity.

Where Calvinism fostered a theology of separation, with the elect versus the damned, Quakerism emphasized unity, empathy, and shared humanity.

Sometimes I’m so proud to be from Philly.

That spirit of care didn’t fade away. Instead, it paved the way for 20th-century reforms that viewed health as a shared public responsibility, rather than just a reward for being a good person.

This legacy still holds true today. When Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare and Medicaid into law in 1965, he was building on a long tradition of compassion rooted in faith, including the work of the Quakers. He drew on the “seeds of compassion and duty” that earlier generations had planted, believing that taking care of the sick and vulnerable wasn’t just a nice thing to do, but a moral obligation.

In this tradition, health is not a reward. It is right, grounded in the sacredness of every person.

Predestination in Policy: The Prosperity Ethic and Medicaid Cuts

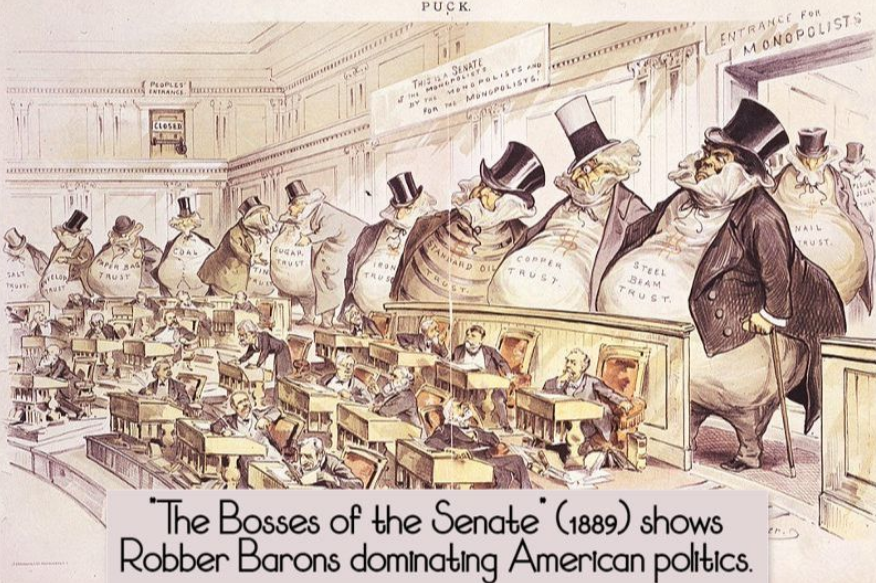

Today, the tug-of-war between these two value systems—compassionate duty versus predestined deservingness—is clearly visible in American public health policy. We see it in debates over whether healthcare is a right or a privilege, and in the arguments surrounding programs like Medicaid. Recent policy moves reveal an implicit throwback to the Calvinist-prosperity mindset: a tendency to categorize people into the “deserving” and the “undeserving” based on their health and economic status.

This is especially evident in the proposed cuts to Medicaid and other safety net programs included in the current budget plans of the Senate and House of Representatives.

The House’s budget, supported by the current federal leadership, includes large cuts to Medicaid, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars, along with tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans.

The contrast is clear: those at the top receive financial relief, while programs helping the poor and sick are targeted for cuts. Supporters of these cuts justify them on moral grounds.

For example, House Speaker Mike Johnson has argued that tightening Medicaid with work requirements is about restoring moral order. “If you are able to work and you refuse to do so, you are defrauding the system,” Johnson said, insisting “there’s a moral component to what we’re doing.” In his view, able-bodied adults who aren’t employed should not receive public healthcare benefits because that would reward idleness – a clear echo of Puritan sensibilities. By “mak[ing] young men work,” Johnson argued, society is doing what’s “good for their dignity.”

The implication is that those who do not work simply don’t deserve the help. This framing draws a line between the “deserving” poor who meet certain moral criteria and the “undeserving” poor who do not.

Indeed, Republican leaders defending the House budget explicitly portray it as protecting benefits for “deserving recipients” while eliminating fraud or dependency. The language could almost have been taken from a colonial sermon or a prosperity pamphlet, it presumes that virtue (like working hard) grants a person the right to survive, and that providing for anyone considered lazy would be an insult to justice.

This value system aligns with the idea of predestination in a social context. If someone is healthy and financially secure (perhaps able to afford private insurance), they are seen as “blessed” and among the elect. Meanwhile, those who are chronically ill or poor and depend on public assistance are subconsciously viewed as destined to their situation. In a predestined universe, trying to “undo” someone’s misfortune might even seem pointless or unwise.

Although few policymakers would state it so bluntly, the underlying attitude persists: good health and prosperity are signs of responsibility and merit, while ill health or poverty are the result of bad choices or even a divinely ordained fate. Therefore, the logic goes, why should the government intervene if someone’s poor health is simply the result of who they are or the life they have led? Such thinking directly connects to the prosperity gospel’s premise that faith and virtue produce blessings – by inversion, a lack of blessings indicates a lack of virtue.

The proposed Medicaid cuts exemplify this philosophy. If enacted, they would likely result in millions of low-income Americans losing their healthcare coverage. This policy effectively says that unless you can demonstrate that you’re “working hard” (and thereby, in the moral view, deserving of help), you shouldn’t count on society to care for you. it is a secular-policy version of saying, “only the ‘elect’ will be saved.”

Those who have the ability to buy private insurance or pay for care out-of-pocket are, in a sense, considered the chosen – they have been “blessed” with resources and will be okay. Those who cannot do so must face the harsh reality of being excluded. This is predestination through public policy: your outcomes are your own, and if misfortune happens to you without the personal means to fix it, that is simply how it is supposed to be.

Challenging the Predestinarian Mindset in Public Health

It is crucial to recognize that these predestinarian values driving policy are choices, not inevitabilities. The United States’ Calvinist heritage may have instilled a strong belief in personal responsibility, but our society also cherishes ideals of equality, mercy, and common welfare. When it comes to public health, the stakes are literally life and death.

Framing health and survival as things only earned by the “worthy” is a dangerous regression. It is immoral

It goes against centuries of moral teachings that encourage communities to look after the sick and vulnerable. Even in early America, where the idea of predestination was widespread, there were compassionate voices calling for caring for everyone. These voices understood, as we must today, that you can’t just preach about moral behavior to achieve perfect health. Illness affects both saints and sinners, and economic struggles often stem from bad luck or systemic problems that are beyond an individual’s control. Public health policies that assume some people “deserve” better health than others are not only heartless—they’re also deeply misguided about how the world works.

The current federal leadership’s approach, implicitly rooted in a “prosperity gospel” value system, may appeal to deeply ingrained American instincts about self-reliance. But we should ask: Is this the values system we want guiding our healthcare policy? Do we truly believe that a diabetic who can’t afford insulin, or a cancer patient on Medicaid, simply isn’t praying hard enough or working hard enough?

Hell no.

Such an implication should offend both our sense of justice and our understanding of faith. As many religious leaders have pointed out, the teachings of compassion demand that we care for “the least of these,” not abandon them. Even some Christian groups are pushing back, “appalled” that budget proposals would gut aid to the poor and sick. They argue, rightly, that mercy and justice should trump any ideological fixation on weeding out the “unworthy.”

Ultimately, America’s Calvinist legacy is a double-edged sword. The focus on hard work and accountability can drive admirable effort and innovation, but taken to an extreme, it can lead to a cold indifference to suffering. The prosperity gospel’s glamour and the harshness of some political rhetoric both stem from that extreme. We must remember the other side of our heritage. the legacy of charity, duty, and shared humanity.

The creation of Medicaid in the 1960s was born from those humane impulses, an understanding that health is a common good and that, as a society, we are “incumbent…to care for fellow citizens” in need. To dismantle such programs in the name of a punishing moralism is to turn our backs on the very idea of a community under God caring for one another.

Cutting Medicaid under an implicit banner of predestination is bad policy. it is a betrayal of the better angels of our nature.

Americans can honor the value of hard work without adopting a harsh view of health destiny. We can reject the idea that only the chosen few deserve security and instead affirm that all lives are worthy of care. In doing so, we support a society that is richer, more compassionate, and more aligned with the core moral teachings shared by both our religious and secular traditions. it is time to break free from the harmful belief of Calvinist destiny in our public health choices and prioritize empathy over exclusion. Our nation’s soul, as well as its health, may depend on it.

Sources

- Starr, Karla. (2020) “Why does the United States lack a social safety net? Blame the Pilgrims.” Medium, 2020.

- Bowler, Kate. (March 2028) “I’m a scholar of the ‘prosperity gospel.’ It took cancer to show me I was in its grip.” Vox, March 12, 2018.

- Harvard Divinity Bulletin. (2022) “Calvin, Capitalism, and Predestination.” bulletin.hds.harvard.edu,. bulletin.hds.harvard.edu

- KFF Health News. (May 17, 2025) “Speaker Johnson Defends Tax Bill Changes To Medicaid, SNAP As ‘Moral’.” Morning Briefing

- Politico. “ (May 23, 2025) Dems roll out ads hitting Republicans on Medicaid.”

- Kitch, Erin. (Sept 2017) “The seeds of compassion and duty: An Early Americanist Take on Healthcare.” Religion & Culture Forum, U. of Chicago,