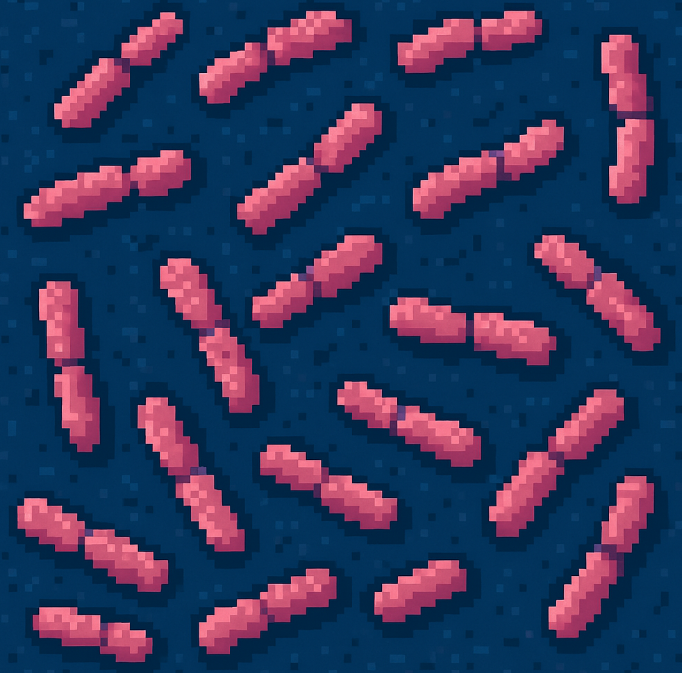

Invasive Strep Doubled in a Decade—Here’s Who’s at Risk

Ten years ago, Group A Streptococcus was mainly something you worried about during flu season—strep throat, maybe scarlet fever. But today, it’s back with a vengeance in a much more dangerous form: invasive group A Streptococcus (GAS). It’s no longer just a nuisance. It’s becoming a public health emergency.

Between 2013 and 2022, invasive GAS infections more than doubled across 10 U.S. states, rising from 3.6 to 8.2 cases per 100,000 people. That might sound small—until you consider this: these aren’t mild infections. We’re talking sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis (aka flesh-eating disease), and streptococcal toxic shock. Nearly 2,000 people in the study died.

And this rise isn’t affecting everyone equally. The highest risks? Older adults, Indigenous communities, people experiencing homelessness, those living in long-term care facilities, and people who inject drugs.

Why Is This Happening Now?

Public health experts have a few theories—and the data tells a compelling story.

One reason is that new bacterial strains are emerging, especially those that attack the skin. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the types of GAS that typically cause sore throats faded. But skin-infecting strains surged. These strains are harder to treat and more likely to infect people with open wounds, poor hygiene access, or weakened immune systems.

At the same time, antibiotic resistance is climbing. Back in 2013, only 13% of tested GAS samples were resistant to commonly used antibiotics like clindamycin. By 2022, that number had climbed to 33%. That’s a red flag for treatment failure—especially in severe cases where fast, effective antibiotics can mean the difference between life and death.

The Human Face of a Statistic

Let’s say you’re a 72-year-old woman in a long-term care facility. You’ve got diabetes and a small pressure sore on your heel. One day you spike a fever. The next day, you’re in the ICU with sepsis from invasive GAS. This isn’t a hypothetical—it’s happening more often, especially in facilities where early detection and wound care can be delayed or inconsistent.

Or consider a man experiencing homelessness. He’s living rough, injecting drugs occasionally, and has an untreated abscess on his arm. He might not seek care until it’s too late—by then, the bacteria may have already entered his bloodstream.

For these and other vulnerable groups, skin breakdown, chronic disease, and limited access to care are dangerous entry points for an aggressive infection.

What the Science Says—and What We Can Do About It

This massive, decade-long study from the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance program involved over 21,000 patients. The findings make one thing clear: this is not just about bacteria—it’s about inequity.

- People who inject drugs were 20 times more likely to get invasive GAS.

- People experiencing homelessness saw a 10-fold increase in GAS infections over the last decade.

- American Indian and Alaska Native adults had infection rates more than four times higher than White adults.

It’s also about infrastructure. Long-term care facilities remain hotbeds for outbreaks, and prevention depends on tight hygiene protocols, early treatment, and wound management—all of which require staffing and training that many facilities struggle to maintain.

What’s Next in the Fight Against Invasive GAS?

Here’s the good news: this isn’t an untreatable infection—not yet. Most GAS strains are still susceptible to penicillin and similar antibiotics. But the rising resistance to frontline treatments like clindamycin and macrolides makes it harder to act quickly and effectively.

So what can we do?

- Surveillance must continue. Knowing where and how the disease spreads allows for targeted responses—especially in high-risk settings like shelters and care facilities.

- Preventive care matters. That includes wound care, chronic disease management, harm reduction for people who inject drugs, and access to clean environments.

- We need a vaccine. Several candidates are in the pipeline, but more research and funding are needed.

- Public health outreach must evolve. Messaging that reaches people where they are—in multiple languages, through trusted community networks—can make the difference between early treatment and late-stage emergency care.

Why This Matters for All of Us

The story of invasive group A Streptococcus is about more than bacteria. It’s about the people society often forgets—and what happens when health systems aren’t built to protect them. It’s about how small cracks in care can let serious infections in.

But it’s also a story of public health vigilance. Thanks to long-term surveillance, we’re not flying blind. We know the warning signs. The question is: will we act on them?

Join the Conversation

How could these findings shape your community’s health priorities?

What prevention strategies do you think are most urgent?

Have you seen invasive GAS infections in your work—and how were they handled?

Let us know in the comments or join the discussion on LinkedIn and Twitter. Let’s keep this conversation alive—and stop the spread before it worsens.

Be the Difference – Subscribe Today!

Don’t get left behind—stay ahead of the latest public health breakthroughs and challenges. Subscribe now for free weekly updates that empower you to take meaningful action.

🔗 Momentum starts with you! Share this blog and help others stay informed.