Talking on The Psychologists Podcast

I was lucky enough to be asked to join Drs. Julia and Gill Strait to talk about community psychology, but also the ways in which implementation can be improved. And, hey!, that’s what we are trying to do here about PubTrawlr. Oh, but we covered so much more ground, including:

- Evolution of substance abuse treatment

- Carl Rogers

- Program evaluation (is it working?)

- Valuing science/EBTs/RCTs *and* lived experiences

- Efficacy (lab) vs. effectiveness (real world)

- Cultural adaptation vs. WEIRD-centric psychological science

- The sunk cost fallacy

- and more, so much more

Listen wherever you get your podcast; but if you’re new to the game, click below to find many different versions. And of course, be sure to rate, review, and subscribe. Julia and Gill are doing yeoman’s work collecting these stories and really trying to push the accessibility of psychological science. So, they also deserve your LinkedIn and/or Twitter follow.

Transcript

I did some editing for clarity, like removing all the natural ways we stumble on our words. If you want to hear those delightful mistakes, well, you have to listen to the audio.

Julia: Welcome to the psychologist podcast. Today, we have Jonathan Scaccia, “Scaccia” like “Geisha” is what he told me to say. Jonathan Scaccia PhD is the principal of the Dawn Chorus Group, which we’ll talk about. He’s a community psychologist and evaluator with 20 or more than 20 years of experience working in community-based settings. His career ban-began as a, I told you, I screw up like the easiest word “began”-as a substance abuse counselor in North Philadelphia. He has extensive experience helping organizations select adapt, implement, and evaluate community-based improvement interventions. Dr. Scaccia also founded the research synthesis website, PubTrawlr which I love keeping up with. And we’ll definitely talk about that as well. So welcome. Hi Jonathan!

Jonathan: Hey Julia. Hey Gill.

Julia: <Laugh> welcome.

Gill: Thanks. Thanks for coming on the show.

Jonathan: Yeah, yeah. Thanks for, thanks for having me. Lots of cool stuff that we can dig into!

Julia: Oh my gosh. There’s already like five things in your bio I wanna ask about, but let me start from the beginning. So what made you interested? Like what are your earliest psychology memories?

Jonathan: Yeah. It’s so I started an undergraduate as an astrophysicist <laugh> and yeah, I mean, I’m still, totally into that and really interested in the super big questions: what is the universe made of? What do we know about where we’re going? And it occurred to me pretty early that my career options were gonna be kind of limited. And I had sort of been, been interested in psychology, but you know, an undergrad psychology education– I, I don’t think, you really gets you into the depth needed and it really doesn’t spark the excitement that would come later.

So I got a degree in psychology and didn’t quite know what I was gonna do with it, and ended up as a research assistant for a group that’s now defunct in Philadelphia called the Treatment Research Institute. And what they did was a lot of studies around substance-using people in treatment settings. So one of our studies was around “why do people enter treatment?”

Another one of our studies –a big, big one was around drug courts. So people who are caught with like a bag of weed, instead of sending ’em to jail for a couple years, maybe we send them to treatment, get them hooked up with different types of case management, and hopefully expunge their record. So I worked with them for, for a couple of years.

And I didn’t realize it at the time, but apparently, the principal investigators on those projects were some real heavy hitters in, in that particular world, the intersection of psychology and law.

Interjection: you can read more about the work of Doug Marlowe and David DeMatteo at those links. Sadly, David Festinger died suddenly last November, which is a freaking gut punch. The guy was always a champion of effective treatment and my professional development. Here’s a wonderful article put out by his institution, PCOM.

And I’ve kept up with them over the years and they just d really amazing things, trying to mainstream treatment as an alternative to legal consequences. So that was pretty cool work. Basically, because of a girl…

Gill. <Laugh>. Always, yeah, yeah, because of a girlfriend.

Jonathan. I thought maybe I need something a little bit more of a full-time job. So I applied at one of the substance abuse treatment sites that we were doing the study at thinking I was gonna be some type of case manager or someone in the back end who’s filing paperwork. But no, in Pennsylvania I was qualified to be a substance abuse counselor

Gill: <Laugh>.

Jonathan: Yeah. Which surprised me. But they threw me into that <laugh> and, really on my first day they had me watch someone do intake assessments, and halfway through the first one, whoever was the coordinator bursts through the door and says, “we’re all backed up. We’re in the weeds. We need you to do one of these right now!”

So I end doing three assessments without ever having a done one on my first day trying to assess if these people meet the criteria for substance abuse treatment. And that was really sort of the story of being in, in this particular field where I worked — a substance abuse and mental health facility.

We served co-occurring patients and we didn’t accept private insurance. We didn’t accept self-pay. Everyone was Medicaid-funded. So these were people coming in really at the end of their rope, really with nothing. And it was just unbelievable, outstanding and fulfilling work, because like people would walk in the door ostensibly with like an alcohol problem or you know, a cocaine or crack cocaine problem–heroin wasn’t actually like a big deal in Philly back then– And really there was just so much room to help people not only get clean, because getting clean is just one piece of the puzzle there, there was room to really help people think through what was important to them and whether or not what they were doing and their behaviors was helping them to achieve their goals.

And, there was a zeitgeist going on in Philly at the time. So addiction treatment for the longest time was rooted in sort of like an alcoholic anonymous model, which is like total abstinence, making amends, you, admitting you have a higher power, and really trying to call people out on their behaviors, so there’s a lot of confrontation in that. And that had been changing really at the vision of a guy named Arthur Evans. Arthur Evans had been the commissioner of mental health in Connecticut when he took over in Philadelphia. And as of today, he’s the CEO of the American psychological association. So not the President, the CEO. So that was the place he went to after this.

Gill: Sounds like, like a, a higher leadership positions

Julia: Yeah. Well, if you’re managing the funds of one of the biggest organizations. Yeah,

Jonathan: Yeah. So, so Arthur Evans really was pioneering. He was a community psychologist by training, which I guess I’ll get to in, in some amount of time. He was a community psychologist by training and really wanted the providers to focus, not so much on symptom reduction, but rather what can we do to enhance wellbeing.

Okay. So what can we do to promote a more holistic view of recovery that I think aligns a lot more with the experiences that people have. So can we recognize recovery as a process where some people are going to relapse, some are not, and that’s okay. We work with their coping skills and their mechanisms as we go along. We also have to recognize that getting someone clean, but sending them back to a neighborhood like Kensington or Frankfurt where there are very few supportive organizations, like that’s not going to help them. That’s going to, to keep them perpetuating behaviors, which may not be aligned with where they want to be.

So how can we align treatment with a more recovery-based model where we’re really trying to promote participation in recovery planning, trying to help people think more broadly about their goals, and trying to promote a sort of drawn from an AA model, peer network, where people are watching out for each other and trying to support one another.

And the organization that I worked for was led by a guy named Joe Schultz, who just retired maybe two weeks ago. And he really super innovative in the ways that he valued, patient or client or consumer or whatever the word is, participation and really try to empower people to take control of their wellness and become positive citizens, not just stop doing dope, but thinking about what they can do to be a positive influence in their community.

Gill: So lemme just try to like jump the for a minute. So the big change was moving from this abstinence model focused solely on being clean and sober to “Let’s focus on wellness.” And if we’re focusing on just overall wellness, then drug and alcohol use will reduce because the person is more aligned with their use and things that are important to them, their own goals. But you’re seeing them as a whole person and not just this one specific symptom.

Jonathan: Yeah. That’s exactly right. And in fact, I would even tell people, like even the 18-year old knuckleheads who would get sent in on their first charge, the court-ordered patients. And I endearingly call them knuckleheads because they’re like adolescents, right?

Gill: Brains aren’t fully developed.

Jonathan: Yeah. And, you know, ” I don’t have a problem, blah, blah, blah, blah,” and fine! Like it, it was really, really cool to meet these guys and women like where they were at and sort of try to work through like…okay. I would say to clients very genuinely, “It doesn’t matter to me whether you keep using substances or not. It’s up to you to decide whether or not that’s going to help or hurt you be the type of person that you want to be.” And like, we, we would explore that together. And it’s very humanistic; like really trying to value people’s true underlying experiences and worth as people. And trying to help them actualize to the extent that they can.

And that’s not to say that we didn’t drop in like the evidence-based practices that we all know. Certainly, there’s so much cognitive treatment floating around Philadelphia because of the influence of the recently deceased Aaron Beck. I think he just died like maybe a couple of months ago. So that definitely pervaded, Philadelphia, and was very effective for a lot of the specific techniques for reducing substance abuse.

But this is just a piece of what we were doing where we’re trying to support people’s growth. And this makes it all sound like it’s like flowers and roses, and it was not. This is an incredibly low-funded, high turnover, high-stress environment. I found myself in a supervisory role probably within five months through attrition, just because of the amount of turnover in direct services there.

But for the people who stayed and who could really sort of like get into the vibe of what was happening, it was just so, so rewarding and so amazing to help support growth. Even though the office that I’m sitting in now is nicer by a magnitude than the facilities we had there. And there’s this sort of a crucible, aspect to that that I look back fondly, and the people that did stay that, that I worked with, they’ve all gone on to really have this real person-focused model.

And it was just wonderful. I mean, just absolutely wonderful, wonderful work. And, you know, I really loved doing it……however <laugh>, it did occur to me after several years that we can get people clean, we can work on these holistic things, but we still have these systemic level problems that are not being solved.

In Philly, the neighborhood of Kensington was, and still is, an open-air drug market with very few things that helped us support what we consider prosocial behavior and so on.

I regret saying this. I don’t know enough about how Kensington has evolved. There is still a misery porn aspect to video of Kensington you can find online, but that shouldn’t detract from the people actually there actually trying to do good work. They’re better people than I am!

And there were potentially better levers that we could hit that helped to magnify the influence that we have on individuals. I started looking into it, and well, “let’s go back to grad school.” Not because I was lost or unsatisfied in my job. It’s just, I thought that there was more that we could do. Like there had to be more that could happen. So this got me introduced to the idea just looking at schools of community psychology, which I did not know existed. And then that brought me down to the University of South Carolina, which

Gill: Go Gamecocks

Jonathan: Go Gamecocks. Yeah. When I applied I didn’t even know where it was. I thought I was in Charleston and I was really excited. <Laugh>

Julia: That’s the only city people know of in South Carolina

Gill: Is that how it happened?

Jonathan: That’s how it happened. Yeah. But Columbia is nice, and through my time there I got exposed to the whole field of community psychology, which is sort of a mishmash of a lot of different fields, or at least it’s felt like a mishmash of a lot of fields since I’ve graduated.

Community Psychology, as I see it

Community psychologists, and I do identify as a community psychologist, we are interested in the ways that we can influence people within the systems in which they live. There’s a couple of other attributes to community psychology that I think are pretty important. The school of community psychology was founded in the sixties. So there was a huge social justice component attached to it. There was a preventative science focus attached to it so that we’re thinking about upstream or social factors that contribute to whether or not you get good mental health outcomes. And because of that, it’s brought me into conversation and work with many, many, many different fields. Just looking at my calendar for this morning I’ve been working with nutritionists, medical doctors, masters of public health, and MPAs.

Gill: Very multidisciplinary,

Jonathan: Yeah. Computer scientists, social workers, education, educational specialists. And it’s really, gratifying that we can be in this place where we, leverage the skill sets across these disciplines to help, to influence social change in where we work. Aa=nd I often say I’m not an unbiased observer in the work that I do. I guess I’m sort of like a hybrid psychologist/activist. Like I want things to get better. Like I want things to improve. And like, because of that, like even the evaluation work that I do is sort of tailored in that way. Like how can we use the best possible methods and the best possible accumulation of data to help different stakeholders move ahead and help to promote health wellbeing broadly defined within the communities in which we live.

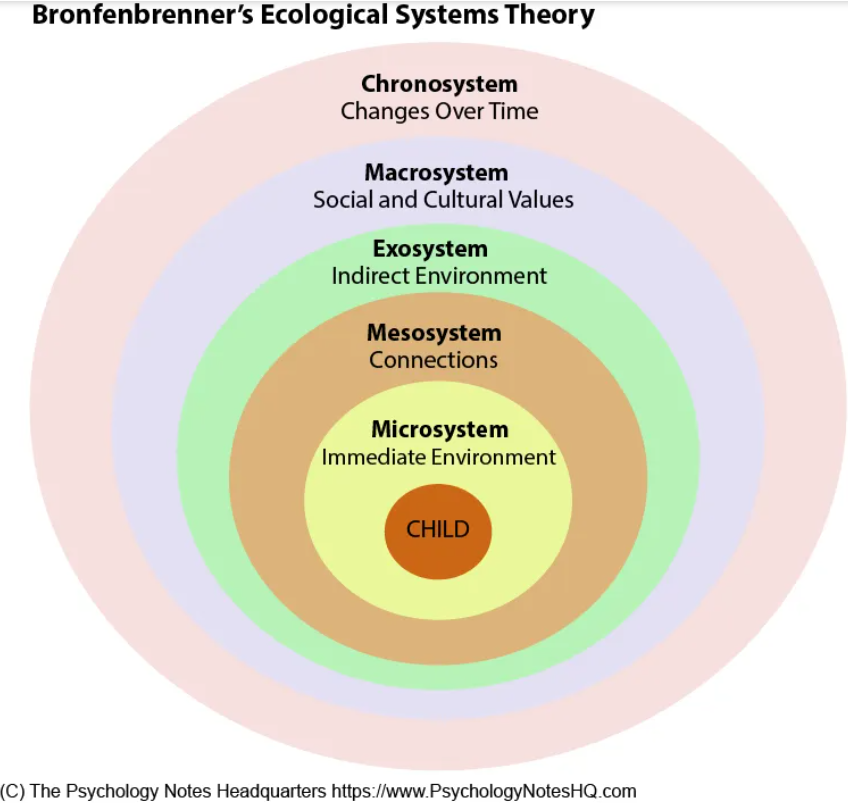

Gill: Let me kinda jump in for a second. You said a lot of things that made me think about a couple things. You mentioned in community psychology, the goal is to help people within the contexts that they live. In that, in that people are influenced by a lot of context. And, and immediately I thought like, Bronfennbrenner and ecological systems theory and the different kind of levels and for like people and, I’m sure there’s a lot more systems theories that are out there, but can you maybe describe, and whether it’s Bronfennbrenner or not, but the different types of environments and in context that people are influenced by and then where are the communities psychologists fitting in? Are they fitting across all those levels or what?

Jonthan: Yeah, sure. So Urie Bronfennbrenner was a Cornell-based psychologist who’s extremely influential. I believe he was into child development but I’m not entirely sure. So he developed this model called the ecological systems model that talked about the different systems that are nested within other systems that influence a variety of different psychological outcomes. So you can have individuals, right. And, he didn’t do this at the time, but this would even include now our genetics and epigenetics and how these impact different types of behaviors and the expressions of different types of….

Gill: ….Of dispositional characteristics.

Jonathan Yeah, and individuals can be nested within families and the family dynamics that impacted our development, and these can be nested within let’s say schools that this is probably an easier way to think about it. And then, what is the leadership and the culture of the school, the teachers, the instructional quality, the conditions and so on, these can be nested within districts and, and so, and…

Gill: They interact with each other, which makes it also like crazy because the schools interact with the families, the government agencies and different things like that. And then government agencies are influenced by political influence and things like that. And here’s this amazing trickle-down effect.

Jonathan: You’re absolutely right. Gill. I mean, it goes all the way up to the sociopolitical climate and even I think Bronfennbrenner maybe even talked about like a Chrono system at some point

Gill: Time

Jonathan: In the time period in which we live. And these, I think he…

Gill: …Added that later in life as he was probably like, oh, shit.

Julia: <Laugh> we got dimension, we’re all gonna die.

Gill: <Laugh>

Jonathan: Well he was probably reading some Earnest Becker or something. So you’re right. These systems interact. And actually been one of the most amazing things that I think you guys are more into this than I am, is the way that our environment actually impacts the expression of our genes. And so on. So it’s like our environment can influence us as individuals from a very genetic level. And yet we, as individuals can influence our systems around us and being able to work with that dynamism and try to model that dynamism, it’s super tough and super awesome as well, because, as much as possible, the projects that I work are in a pretty weirdly broad portfolio.

So I work in vaccine hesitancy and community coalitions and school safety and research synthesis across, all of these different domains where can we, as much as possible, have the most influence over our outcomes, where are our good leverage points to hit? And these change–because what works for people in Galveston, Texas is not going to work for a community of Hmong immigrants in Wisconsin. And this is where the excitement, at least for me, is in community psychology.

How do we take these best practices –like cognitive behavioral therapy is a best practice. How do we take these things and try to translate them and adapt them and make these things work at scale within these very specialized communities? And how do we do this in a dynamic and bidirectional way where we’re really trying to bring in the voice and the experiences of the people that we’re working with? Because I’m just some moron who sits in my ivory tower and reads our articles. I don’t know what people’s real lives are like, and the real things that are of concern to them. So I have to shut up and like, I’m not doing now, shut up and listen.

Gill: We did this podcast for all the psychologists to be able to come on and, and talk because most listen, most of the time; we listen, right?

Jonathan: Yeah. So I have to be able to listen to the community and what their needs are, and what’s gonna be helpful to them and sort of craft the interventions that make the most sense for them and have the greatest resonance for what they’re trying to do.

Julia: Is this all part Jonathan of the Dawn Chorus Group, can you tell us a little bit more about the logistics of the projects that you just mentioned. Are those all program eval things, and if so, what is that for? Say for Nancy in Ohio who doesn’t know what that is?

Gill: Not, not cousin Nancy. Oh my God.

Julia: <Laugh>

Jonathan: Yeah. So I have an independent research and evaluation firm called the Dawn Chorus Group named after not just the Thom Yorke song, but also the beautiful cacophony that happens on spring mornings. It seemed like a good metaphor for digging through a lot of data.

Julia: Oh.

Jonathan: But so, I can describe myself in this podcast is like, I get to be a practical academic without having to worry about being at an institution. So most of our work is grant or contract-based, mostly funded through relationships we’ve developed over the years. And it is primarily program evaluation work, but it’s formative evaluation work. So what that means is like, we are basically studying what’s happening in different programs.

So there’s a program right now being funded by the CDC that’s giving different community coalitions, resources to improve their outreach to improve vaccination rates and underserved populations. So we study how they do that. We have a series of questions that we’re interested in and then develop methods to answer those questions.

And we can have the freedom to do pretty interesting things to get at that. So some of it is traditional like here is a survey: “tell us what strategies you’re using.” But I’m actually getting really bored with surveys these days <laugh>. The way that I try to set up my work is a mix of high and low-level data. And I’ve never been able to come with a better phrase than that. The high-level data is what can we get through already existing sources. We can web scrape and use computers to pull data from the data people are already collecting or leverage already existing data sets out there to tell us about community context and can we also pair that with what I would consider sort of the deep, almost ethnographic type of work qualitatively.

Can we just sit down and this is where I would shut up. <Laugh> sit down and just hear people’s stories about what’s going on. Like a semi-structured interview, I guess. But I like to just hear what’s going on and hear what’s their story is and how this is impacting their work. And I try to be as open as possible in those encounters, because you never know what will help to raise our understanding of what’s going on. And to back up like a minute and a half, we do formative evaluation because we’re trying to help these people.

There is a absolutely a place for the type of research where you are randomly assigning participants, you’re intervening with one group, and then you’re measuring sort of the difference in outcomes-based off that, right? 100% we need that work; that needs to be funded.

What I do is build infrastructures within these organizations and communities to help them learn and iterate and improve along the way so that they can reach their outcomes so that they can tell their story to sustain their work. We can give them data points sometimes that helps them tell their story. Sometimes it’s like capturing a really powerful moment about how a mother had not been able to afford her rent, but by connecting to a certain program they now have stable housing, which allows their children to be in school more regularly.

These are the types of things that really can influence change because they have that emotional valence to it. And we really respond. So with Dawn Chorus, that’s what I do. I get to work on these fun projects all day, where we just get to learn and we get to talk to people and we get to try and think creatively about how to answer different questions pertaining to how well a program is working. It’s remarkable really that this type of job somehow existed and

Julia: <Laugh> you created.

Jonathan: Yeah, I was able to find my way because all I get to do is think….

Gill: …and think about how to help programs that already exist. Yeah. That is out there trying to serve and help people. And you’re helping them create those continuous kinds of cycles of improvement with data on outcomes that they’re interested in. And you’re trying to capture what they’re doing. And then you get to provide that data back to them, which can a help them tell their story, but also help them be like, “you know, maybe this thing’s not working, but this would.”

Jonathan: That’s right. And the psychologist in me can bring that to the table as well. There are types of like evaluation models where you just provide the data and get out of the way. But I have some expertise, I think, in certain areas. So I can be one, not the only, voice at the table to help guide some of this work. And that’s where it’s fun because we work in evaluation, at least in the projects that, that I get to be involved in, or that I choose to be involved in, evaluation is, part of the overall program team. We really try to interface with the funders, the people implementing the program, the people on the ground, and, help them get to some sort of consensus on where they want to go.

Gill: I think it’s important because we talk about program evaluation in my classes a lot. I actually teach some program eval mixed with consultation. And I sometimes like with our students are like looking at me like, when am I, when am I gonna do this? When am I, when am I gonna actually make a logic model for a program, figure out things that we can….

Julia:….Can I back up a little bit for, like, I know we have a lot of people that listen that are just like friends with us. We’re saying program evaluation and even the word evaluation. Let me just rewind a little bit again. So if you think about, for most people, like where would you have seen assessment probably when you were a kid in school, right? so that kind of assessment is usually what’s called summative assessment– at the end of the year, you get a grade or you pass or whatever, it’s like you said, you get the data and you get out and it’s either you pass or who failed or and you get to go to Harvard or you don’t and that’s the end of the day.

And in psychology, as you were saying, just to kind further explicate this, a lot of randomized controlled trials, things like that, is at the end of a research program where all the iterative work hopefully was already done. And we’re saying just, did it work or not?

And there’s not many mechanisms for feedback. Whereas formative would be like, “Hey, here’s your progress report?” If I’m trying to relate it to like a classroom, let me just talk to this kid real quick and figure out how much he’s understanding about the unit. So I can figure out what I still need to teach him, what he still needs to work on. Things like that. It’s not, “here’s your data you’re done.”

So when y’all are talking about program evaluation, schools are always my context, but like when I was a teacher of one of the schools I was at adopted this big suicide prevention program. And it cost millions of dollars. And so like at some point, my guess is that that district would have someone come and say, “okay, is this working, and define what that means?”

What are the variables? We’re gonna look out what are the outcomes, whatever. Most programming eval, as we were taught in school, psych is summative in saying, “okay, this is the summary–it’s over. Does it work? Or doesn’t. “

And I will say in schools, a lot of times what happens is we throw the whole thing out and then we get a whole new program. And what you’re saying is very different, because you’re working within the existing structures within that fabric. And you’re making small iterations that maybe don’t have the kind of control you’d want in like a vaccine trial. But we’re not talking about a vaccine or a molecule. We’re talking about people and communities, which is complex. And so you can’t really come in and say, “here’s the data I’m out.” It’s like it almost to me requires that level of complexity, that level of subjectivity, because you can’t just say like, “95% of students pass. We’re done. You’re good. All these of people quit drinking, great job.”

Gill: But you’re evaluating the critical processes that occur in the program and things like acceptability and like different views of the program, because all of those things influence whether a program works and all that’s ongoing. If you’re meeting with someone weekly, that’s every day and that’s what that formative piece is.

And I think I was going to go with a little bit of that point. You mentioned the need for RCTs– randomized control trials. We talk about efficacy versus effectiveness. And I think for a lot of people, those are just words on the page. I mean they get an efficacy trial or randomized control, highly controlled. And then that effectiveness piece is how is it actually working in the real world?

Oftentimes I think, I feel like at least when I was in grad school, I was so RCT-focused. That was what I thought of. Then, you learn, “okay, well actually there’s already a lot of programs that exist in the real world or we’re moving something from that kinda R C T experimental stage into trying to scale up and disseminate into communities. And then how does that actually work?”

Because it is completely different when the researchers aren’t in control of implementing. So I could wax on, but I’ll stop for a moment.

Jonathan: It’s important because there are trade-offs in this type of work. I can’t make good statements about causality in the work that I do because there’s just so much that confounds it and fidelity– doing things as intended– fidelity gets thrown out the window. And that’s a trade-off that at least in this type of work I’m okay making.

And it just does not replace the need for some of these other types of things. When you were mentioning a suicide prevention program, Julia, like a couple of things came to mind. I thought, “could you like, could you formative like evaluate that?” Suicides are, you know, thankfully like a rare event to begin with. However like one event is too many. Would you make changes already based off of that?

When reviewing the transcript, I wasn’t satisfied with this example. Could you formatively evaluate a suicide prevention program? I found this super recent article, but this is more about evaluating a training, not the program itself. In many organizations, a “seminal event” like suicide or patient death triggers a quality improvement review or after-action report. But that’s not really formative evaluation, though….

And then there’s also when you’re saying the school district is investing a certain amount of money or stuff into this. Luckily some of my work, but not a lot of it, spills over into a small-p political context where there are many different sorts of stakeholder interests involved in something that potentially impacts the types of questions that are asked. So you’re right. School districts– we’ll put something into place and then see if it works or not, and then try something else. And that, in many cases they could benefit from a more formative approach:

Sidebar. so I’m a five-time failed candidate for my own school board.

Julia: Five times: You’ve run five times for the school board.

Note: Here’s link to the most recent interview I had. It was recorded, with a transcript.

Jonathan: So run once and I’ve interviewed for vacancies the remaining times. And every time, I try and get in front of them, I make the argument that you need to have a more improvement methodology. Be willing not fall into like the sunk cost fallacy with different programs and really try to think critically about what’s going to best serve.

Julia: Can you quickly tell us what that is?

Getting away from the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Jonathan: Yeah. so the sunk cost fallacy is one of these, traditional cognitive biases, where you are more likely to persist in an activity if you have devoted a much or a large amount of resources to it. So let’s say I spend $2,000 on a project management software that is just absolutely terrible. I’m more likely to stick, around with that than get a new one because of the money that I’ve put in

Gill: But like time is included. So I have the theory for an example that is maybe based on this. We and maybe I shouldn’t say “we”, we were looking for job candidates for a professor position at UHCL and the year before we did a big search and we hired four people, everything was virtual, right? All the interviews were virtual, but every, everybody, all of the colleges were doing virtual interviews because they had to.

Now this year it was a little bit, you didn’t know, because some places this could do in person, some could do virtual. Our university chose to do all virtual interviews and we were unable to fill those positions though. We had a couple of really good candidates. One of my theories though, partially, is if you have a candidate and they had have two job interviews, you know, and if you ever do an academic interview, it’s like a whole day. It’s a big thing. And one of those interviews you have to get in a plane, you gotta fly. You gotta stay every night. You gotta, you gotta put on pants. <Laugh>, you know, you gotta wear pants, you gotta take off work, you know, and you gotta then sit and go walk around the campuses, go into different offices. Yeah. It’s a lot of time and effort. You, you gotta do all this stuff. Then, then come back to your hotel. It might even be something the next day or you wake up.

Then the other interview–you wake up, you drink your coffee, you get halfway dressed. I mean, I know they’re wearing pants, but anyway yeah. And you’re just at your computer for five hours and then you’re done at the end of the day, if you have both options and everything’s equal, which one are you most likely gonna choose if all experiences were well? Probably the one you put in all that effort.

Jonathan: That’s a definitely a good example and it made me think about like my own hiring process. The candidates that I spend more time getting to know aspect versus trying to find sort of someone who might have like the best set of skills. Hopefully, time is correlated with quality. But it may not be. So yeah, that sunk cost thing is definitely the case in so many different public initiatives, and, this is where, I hope that some of the work of communities, like colleges in general, can be influential in trying to like norm the uptake of evidence and how we use different things and how we can try to implement more effectively.

And as you guys know, the last couple years, we’re fighting a mis and disinformation pandemic And the challenge is that we have to norm and get back to the use of science and the intelligent use of science–not treating as like an ideology, but rather a set of methods that helped us answer questions in a critical way. That’s a challenging frontier that we have to navigate going forward.

Gill: I mean, there is so much information out the there, and going back to what you were mentioning about like the school boards and I’m sure this comes up in your work is that with the sunk cost analogy,, there’s also this piece of having to admit from a programmatic systems change standpoint that maybe something wasn’t working, that maybe you’ve been doing for a long time, and that’s hard for an individual,

Julia: But that’s why it’s a fallacy. Economically, and financially, the sunk cost fallacy is a fallacy because tech in an economic sense the school district will be right to abandon that program and try again, because the idea is that the mere fact that you’ve pumped money and time into something does not make it probabilistically more likely to be effective.

Just like the people that came to your interview. They actually no more likely, or not from an economic standpoint to succeed in that job, just because they spent more time there. But the trap is that you fall into like, “oh, I spent all this time and money.”

So I guess what I was gonna kind of flip it and ask you guys is since that’s technically like a fallacy, in a logical/rhetorical sense, it’s a fallacy because we kind of have this bias, but by the same token, some cognitive biases or heuristics or rules of them, I mean, just like we feel the need to categorize things, but that goes terribly wrong when we categorize race or how is that kind of hinging here where you have, “yes, it’s a fallacy economically, and that, you know, if I buy a $300,000 car <laugh>”, (that will never happen), but like I get in wreck the idea being, it’s easier to see in like a purely financial example, but like, do I fix that car, which might cost $400,000? Or do I just get a new car? Well, I just probably, I just get a new car that makes financial sense. But when we’re talking again, we’re talking about people and things that already exist and programs and things that are not perfectly designed and that aren’t purely economic, right. We aren’t, what is it?

So economics, all this stuff about, like, we don’t actually think that rationally and things actually aren’t that rational. So I guess I would just throw that in there of like, what do you all think about this iterativeness being messy and, and science being messy? I think that just on something Jonathan was saying, like right now, science is being treated as sort of an ideology or like one way of viewing the world. And, and maybe it’s not that, and we can’t just go around applying these different, like, purists, I think I’m getting lost in my question…..

Jonathan: I love that. And I wish I like was better at sort of adopting like not a straight behavioral economics approach, but really being much more sophisticated in how we communicate and work with people that recognize these different, what Kahneman would say, these different systems.

Look, we’re all on the same team. We’re trying to get good things to happen with the people that we work with. So I from a good faith effort we want to find the best possible way to get there. And, you know, we’re trained in sort of this scientists/scientism- type of way where we’re logically presenting evidence and controlling for that.

And yet there’s these other types of ways that people come to make decisions that we maybe don’t leverage enough and that like to travel all the way back to like the beginning of our conversation. This is where we as a profession, psychologists at large, could benefit from thinking more like what marketers do.

How do we potentially help to communicate more effectively with people in a way that speaks to them and speaks to their values and helps us to cultivate conditions that are aligned with a particular community’s values. I don’t want to get into socially engineering society, I just want to…..

Gill: ….a culturally adapting thing, like programs to. To meet the needs of the populations we’re trying to serve. And not just assume that we know better when we haven’t lived, when those values, some of those values and, and neighborhoods and communities are different than the values we were raised on are you were raised on our dream was raised on,

Julia: I think is why people see the scientism ideology kind of thing. Now, the mistrust of institutions, I think that’s a direct result of that because we’ve overstated the importance of top-down advice and public health messaging. That’s top-down. “We know this is true. So we’re gonna tell you.”

I think what’s coming to light is science is messy. Things like this are messy. It’s not that we know the right answer and we’re top-down trying to force it on people. It’s and what y’all been speaking to, right? Like this is a more organic like grass. Now, we also have to have the bottom-up view of “this is your community’s experience.” And I think why people are mistrusting institutions right now is because they view it more as, no, we’re just right.”

We’re doing top down. We don’t care about bottom-up. We don’t care what, you say, we’re going to tell you what’s the right thing to do. And like you said, I think there’s a place for RCTs. And those vaccines got developed really quickly because of that kind of science, but there’s also when you’re not a molecule or an atom or a virus, like, there is an importance to, as Jonathan said, like having both the top-down and the bottom up are really important and we can’t just throw away whole perspectives. Because we don’t.

Gill: You can have a vaccine that saves lives, but people would still have to take it. And, and, and It has to,

Jonathan: Yeah. And I want to back up off that off slightly. Like I don’t believe all perspectives in all evidence are equal. So I’m not like a, what was that a positivist? There is some sort of objective evidence and truth out there. And, maybe it’s just acknowledging that when we work with communities that it’s, not enough. It’s not sufficient just to say, “this is what works,” there’s all sorts of other stuff that has to be, has to be addressed if we want to help promote change.

Julia: Right. Yeah. Like kind of both honoring both.

Gill: Ultimately, it’s saying, you know your community, you know your family, we also have information that we want to share like that we have special training in, like the researchers, the psychologists, right> And that we have this information, we would like to share it with you so that you could use it. To help your community well.

Julia: I want it to make…

Gill: ….sense for you. It’s gotta make sense to you. And maybe some of it won’t align, but maybe there’s something in there, because it’s a lot of information. I mean mental health interventions–take cognitive behavioral therapy. How many different CBT interventions are there out there?

Gill: Millions. I mean, they not really millions, but you know, but just a lot of, a lot of variations in there, parts of CBT that can be helpful without the whole model

Jonathan: That’s what you studied, Gill? You were into like behavioral kernels, I think.

Julia: Walking right into his well.

Gill: We have youth mentoring programs that are modular in that sense that we have different types of sessions that we can pull from our like session activities and things that we can pull from based on the kids’ goals and their values. And some things come from CBT. Some things come from academic interventions, like using flashcards, like if their goal is, you know, I want to get an A in math or….

Julia: ….some of it’s like mindful or, you know, emotional.

Gill: And so it’s kind of like that, but at the same time, even within some of those practice elements, most of our evidence-based interventions come from a Euro viewpoint. And oftentimes the communities that are in the most need are under-resourced, low SES, which are minoritized groups who might have different values that are ingrained to this mental health scene.

Jonathan: Oh, oh boy. How much time do we have? <laugh>

Julia: I wanna walk out, you guys, go ahead.

Jonathan: For posterity, I want to say this because you hit on one of my huge, huge drivers and there’s a lot of my work actually is, is from like a meta sense is, is concerned about that issue.

So we know that the organizations that could most benefit from resources or technical assistance or coaching, you know, don’t have the capacity to get additional resources. They don’t have the capacity to apply for that. So they don’t get the funds either from the government or from private endowments. So you get this sort of this paradox where the best of the best are getting resources over and over again.

And some buddies of mine, at Rutgers-Camden showed that like we, we can identify areas of health disparities and, show that these are places that are getting less resources from philanthropic and governmental sources.

Have to sidebar here to call out, again, this wonderful paper by Bob Atkins and Team. I was going to find a link, but it turns out there’s a live link to download the pdf. So, if you click on below, it will download the pdf.

So we’ve got this whole field now. And how do we make more effective grants in building up organizations so that we can better serve people in these populations? And then what you were saying about like us being WEIRD, you know, the, the westernized, all of our science being like Westernized, Educated Industrialized, Rich and Democratic: I think like that’s super troubling to me because, what, we have 330 million people in America? That’s probably in the ballpark.

Gill: That’s a good estimate.

Jonathan: <Laugh> This is one of my soap boxes. The stuff we do is a public good. This is not like something that should be commercialized technology. This is something that can help people live better and happier and healthier lives. A lot of the science that we do, health sciences specifically. Let’s try our best to get that out there, to get it into formats that is acceptable and that can be uptaken by people in very, very diverse cultures.

And maybe it’s gonna work. Maybe it’s not gonna work. Because of these conditions we’ve talked about, , during the course of our conversation. But I just do not like the idea of this stuff just hanging around here. It just seems immoral that the stuff that we know works does not have a wider reach. I really want to try and address that and change that. And in a lot of stuff.

Talking Therapy

Julia: Let me ask you: I know both of you are very systems, meta, dudes, but thinking about how you were once a substance use counselor <laugh> right. Thinking about being in the chair of a therapist, or even as a client, like, you know, we’re talking about interventions that are “evidence based” versus things that people will actually do. And I wonder if you have thoughts about like, why this debate matters at an individual? So if I’m someone that’s just like seeking services, I have a problem with alcohol or drugs or whatever. Like, why does this matter to the individual person, to the individual clinician? Like these sort of, you know, everything we’ve talked like, the debates, the overall science, the data stuff, why does that matter to an individual who’s actually struggling? If that makes sense, like on an individual level?

It might be a long answer. <Laugh>

Jonathan: Well, I’ll try and make it short. I think it’s just disrespectful. There is an explicit contract between, between counselor or clinician and patient where the contract is “I share, and you help me to resolve these issues.” And lif we’re not going to be using the best possible strategies to get there, and “best” can be qualified in a lot of different ways, it seems disrespectful. It seems inefficient. It just doesn’t seem right.

Julia: Like I’m not even worried about evidence-based interventions or what works. I’m just really only worried about that bottom-up part, you know, like, are you saying kind of throwing out th….not using the best we have.

Jonathan: I think there’s plenty of studies that show that like the nonspecific factors in a clinical relationship are really important. So like the rapport that gets developed and the, the empathy and the, the relationship. Yeah. But that’s not gonna, that’s not going to do, do the trick.

Not enough, even the St. Carl Rogers, if you would go back and like, watch the tapes of what, like Rogers was doing. I mean, he wasn’t, he wasn’t just parroting back. I mean, he was emphasizing different things. He was moving people in different directions and he didn’t realize this at the time, or didn’t explicitly like, argue it, but he was, he was doing some like proto-MI types of types of stuff. I mean, and this is where, you could develop an AI bot to just sort of deliver reflections.

Gill: I actually think there may be, I know there’s an, I know someone in the UK was developing a motivational interviewing app a while ago, and I think it probably is out there.

Julia: But, but Carl Rogers would be someone. So you’re saying that because I’m just trying to think of people who don’t know these, I’m thinking about my mom and dad, right. Being like what are you talking about.

So Carl Rogers supposedly was someone who, you know, didn’t use CBT, or tips and tricks or, or strategies. Supposedly a lot of counselors see Carl Rogers, client-centered, person-centered, no, it’s all about not directing the person, letting them lead you, blah blah.

And it almost sounds like that’s not like anti-science or anti-evidence, but that a lot of counselors now I think, do identify primarily that way, a person-centered where it’s not like techniques or whatever. But, but interestingly, Jonathan, when you, as you said, there is a lot of research about common factors or non-specific factors in the helping relationship. And there’s also some really interesting research that what people say, “oh, I’m person-centered I don’t direct, I don’t lead.” If you actually code their behaviors in therapy, like you said, like they’re not being completely person-centered. They might have an idea that they’re being completely person-entered or not doing tricks or not doing when we say interventions, by the way. I remember when I started grad school, I was like, what does that mean? Like the show or what any, an intervention could be like a two-second thing in therapy where you say like, what are you grateful for today? So any little move you make in therapy is an intervention just to clarify.

But yeah, I think what you’re saying is like even someone who we hail as look at this person who just cares so much about the lived experience and is not trying to do strategies, actually, he was like, actually, you do need that of it. You need the facts you need, you know, the, the part that was designed from the RCT or the molecule or whatever, it’s necessary to have the relationships and the contextual factors. And it’s also necessary to have some kind of active ingredient in your treatment.

Jonathan: Yeah. I’m with you 100% on that.

Julia: So I guess for an individual who’s coming to you and is like, I’m struggling with drugs, whatever, all that is to say, you wanna make sure it’s both acceptable and effective, like working. But what we’re saying is that up to now a lot of programs and a lot of top-down things have ignored completely the, relationship piece and have just said, no, just walk in and do these things. You know, it doesn’t matter, you know, if they’re actually gonna take the medicine or if they’re gonna listen to you or whatever, like just do these things. And that is what people push against. And like, that’s not enough either, I guess.

Jonathan: Yeah. I think it’s actually like probably equal parts, both. Like, I’ve certainly been around enough like programs where there is a little bit of like the Polyanna-ish, like, well, you’ve got this idea, let’s try it out. And, you sort of doing things in a way that maybe there’s not a solid theory of change behind it, or like, there’s not like, there’s not like a rationale for like, wait, why are we meeting with these people like four times a week? And right. Like,

Julia: The coloring used to drive me crazy.

Jonathan: I’m open to sort of exploring that. What is the mode of the change that we expect to see because of this and a lot of programs don’t have that. So it does go both ways. It’s not just like, you know, we are guilty of dropping things into communities and expecting them to work. And I think a lot of like, community coalitions are guilty of thinking that, you know, just because they’re doing something, they’re doing something right.

Gill: Because it sounds good. Or are the activities sound good or something like that, but maybe, but there’s no real clear reason to why they think it would actually improve someone’s mental health, their wellness. But that is where you come in and you are trying to bridge that gap.

So the thread again,– there are things that are evidence-based and there are things that we can adapt to make it more acceptable. Again, back to the population you’re trying to serve, because we realize that, you know, there are biases in the development of ideas and that mental health wellness, all of those things, it is a social construct. And so therefore, you know, if we’re already considering that there are ideas about norms and what works.

And obviously we have numbers to help back some of that up. But mental health still add up as a whole is a social construct. It’s very subjective. Like wellbeing is a very subjective experience for people. And so finding that line and that balance is a, I think what you have to do to be able to get those practices in people’s hands

Steve Jobs realized if I want to get phones or iPods into people’s hands, it’s gotta feel nice. It’s gotta look nice. It’s gotta hold in their hand and make them want to use it. Because, I already know the tech; it works. And the reason virtual reality doesn’t work right now. I mean, or why no one is high on META is because right now you have to strap a giant thing to your freaking face.

Like basically where football helmets to like go into the virtual world. But once they have like Ray-bans, which they actually have Ray bans that take pictures and do sounds once they have Ray-bans and it’s easier to have it on glasses other than hold your phone, then you might see like a change.

Jonathan: You’re getting at like the user experience, user interface for a lot of different interventions. I’m not telling tales out of a school here. Like I was involved in a very large project, maybe about five years ago where we were working with military bases and we were working with every military base within a specific branch and we were helping them develop prevention programs. And the way that we were doing that was handing out worksheets for them to fill out like, <laugh>, this is not the way that people work. And they approach like a planning process. And even at the time, it just seemed so like bonkers that like, even though the process that we were using had studies that said it was going to work.

It just the way that people were approaching engaging with that intervention much like putting on a huge headset is just so……I don’t know even know what the right word is,…it’s juvenile or, antiquated or just ineffective,.

Just the fact that we were using worksheets, it just, just drove me, drove me insane. And, and I think that in our social services in general, like one of our frontiers is how do we incorporate a lot of the different things that comes out of like industrial psychology like human factors or things like that better account for the ways that people potentially interact with things or interact with interventions writ large. I think , that’s a critical part that we still have a lot of work to do, which is good because I plan on living longer and want more things to do.

Talking PubTrawlr

Julia: Well, maybe that’s a good transition. So speaking of the importance of people having the evidence, you know, in their hands, tell me about PubTrawlr.

Jonathan: Sure! So there’s a lot of things that go wrong between when something is published and when it gets used, and this is a whole field called implementation science that I could go into, but I’ll just sort of leave there. And there’s a pretty robust statistic that it can take up to 17 years for ideas to sort of filter out. And yeah, it’s a long time. I sometimes like to think about like, what albums was I listening to back in 2005? And there was some great stuff in 2005, but what, what if I was just listening to it today?

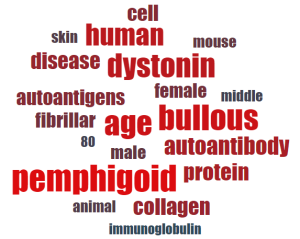

So what PubTrawlr does is use a subset of artificial intelligence called natural language processing to synthesize large amounts of scientific metadata.

So to say that in plain language because I’m not <laugh>, I’m not the marketer here. But basically we take a lot of articles, sometimes into the thousands and try to distill it down to what the core message is. What are the themes and trends here? What are the key articles based on a variety of different metrics? So we reduce the tension and the intimidation involved with engaging with the scientific literature. We’re trying to make it easier for people to see what’s out there. Let me get closer to this.

So if you go to, pubtrawlr.com, we have a free version that we’ll be pushing live soon that you can pull up to 250 articles to tell you what’s the main story. And then we actually integrate some stuff from a group called the community commons, to show some potential strategies that are related to what you’ve searched for? A

The technician in me: I want to do a lot more to integrate and connect to best practices for what people search for. And there are a lot of repositories out there that we’re working on. I want to do more in terms of the ways that we extract data from articles so that we can try to you know, automate the meta-analysis process.

I don’t know if that’s four years away or 10 years away, there some people I’m working with at Lehigh who do some good work with extracting data from tables, which is usually used for meta-analysis. But I’m sort of going into the weeds here. The idea is just like, “Hey, let’s try and make looking at the primary science, more fun and exciting easier, easier to play around with.” And you know, that’s, that’s the story there.

Gill: It’s AI-based, there’s an algorithm that really just tries to just get the big point across from such large fields of research. So many papers. It is intimidating to do that. I will say it’s intimidating to find a movie on Netflix because there’s so many things and, and there’s automation in that where they try to kind of like recommend, obviously that’s more tailored to you in your interest. But what you’re saying is that you can go into this system type into subject that you’re interested about and it can, and it can pull some information and give you common themes.

Jonathan: Oh, this is where this the bottom-up part again comes up. I absolutely want to try and build have sort of an architecture for this” recommendation system into best practices”. So that if we have enough data at scale where we have, let’s say people are searching for depression and we have a list of like strategies and people say like, oh, thumbs up. This is good. Thumbs down. This is bad. This is sort of reductionistic, but not that much. If we can apply that at scale, can we then develop a feedback loop where we’re really trying to get incorporate the community-based perspective about what’s working and what’s not working. And there are certain areas this is a little easier to do than others.

I actually would be, for obvious reasons, cautious about providing community-based recommendations for medical conditions, but maybe for things that are more like capacity building. So some of the stuff in coalitions might be a little bit easier with change management strategies.

But in general, the algorithm that you’re talking about, Gil: I think is super underutilized. In this CDC project I’m working on now, we have a list of like, let’s say, 30,000 respondents. And in addition to talking about vaccine-related stuff, they can identify different social needs. They say, “I have a need for vaccines,” or “utilities, or I have a need for rent, I have a need for childcare, et cetera, et cetera.”

So what we can do is do an analysis called market basket analysis, where we look at the co-occurrence and the ways that these things fit together. It’s scaled and use that in a predictive way to say where people might also have holes.

So if you go to the grocery store and you buy you know, noodles, Parmesan cheese, and oregano, it’s likely though not 100%, but it’s likely you might also buy spaghetti sauce. So if we can identify different clusters of needs that people have, can we more effectively route them than to the social services that would meet those needs? If we sort of understand what’s going on there. So, I’m really, really excited about doing that type of work, because….. I forget maybe I said it on this podcast already.

….I think that social services is at least 20 years behind where customer service is its use of data and and AI, and there is just so much opportunity for us to be more effective and efficient in the supports that we provide the people. Not because we’re trying to be prescriptive in what we, but we can be better at what we do. And there’s so much information out there that is untapped that I think we can, we can reduce the fluffiness of a lot of what we do and be more proactive.

Gill: That would be an amazing type of site for the consumer and the person in need a mental health practice. Is that because is that, is that, that’s kind of what you’re saying. Like they could go in, but I, I kind of got a little confused too, if it’s both for like the practitioner and the researcher who can go in and they’re looking up certain things, and you’re like, you know, what, if you’re looking up positive behavioral support systems in schools, you’re probably also like also interested or might be dealing with manifest determination. I’m just kind of making up some like school psych kind of issues, but then there’s also the person who’s like, I need I’m, I’m looking for a Dr. like a substance abuse counselor and this, and then maybe there’s, I…..

Julia: I feel that link. I feel like there’s a lot of startup software companies that are trying to come from the consumer end of it, right. Like, oh, we’ll match you with a therapist. We’ll match you with a service, whatever. But I think what maybe what you’re saying is more like a system bundling, like, like if I’m a social worker, I’m a psychologist and I’m working with someone, or if I’m like a community coalition leaders, are you saying more at that level, like the group systemic level, that system would work better?

Jonathan: Yeah, it’s not just matching based on characteristics,

Julia: Not like precision medicine or whatever.

Jonathan: That’s an easier or more straightforward problem. This is more can we anticipate and evolve what our needs are based on what we’re seeing as effective implementations in the past. And to me, that is super exciting. That’s one of the frontiers that I hope I’m working on.

Julia: Sounds like you …

Gill: …Well, you’re already doing it. And, and so it’s pubtrawlr.com, and, and, and it, it is not pub crawler. Cause Julia kept telling me pub crawler. No. And I was like, no way it’s called pub crawler. Cuz that sounds like, like, like I do

Julia: Not make these kinds of phonetic mistakes,

Gill: But then I was like, that would be a good website. If there’s not already one, I would assume there might be a pub crawler.

Julia: I think you heard that.

Gill: Pub crawler.

Jonathan: You were the fifth person in three days to mention that association and you know, pub crawler. Like I could go onto like the derivation of all of it, you know. We’re going to have to transition to like PT research or something like that. <Laugh> in the future.

Julia: I like it. We’ll certainly put a link to that. I know that we’re up against the hard stop for you and for us. But we would love to have you back and talk about more big data stuff and all of that. I hope that you can figure out all these things, Jonathan on your own so that, you know, the system can get better.

Jonathan: Dude, we have so much, it’s not on my own. Like there’s so many…

Julia: <Laugh>

Jonathan: Like I made, I made a pledge to myself a couple of years ago that I’m only gonna do cool things with cool people. And this is cool. There’s lots of people working in these problems and it’s a credit to them that I get to sort of stand on the shoulders of really, really smart people and just sort of put it together in whatever combination I have. So thank you for having, having me on

Gill: Yeah. Thank you. Before you go, though, I, you gotta, let me take a picture of the screen because we have our microphone set up a little differently. It looks like you’re and, and it looks like whenever you’re talking that you’re leaning into our microphone. It’s awesome. I’ll be sure to share it with you. We’ll you maybe it’ll go on the site.

Julia: Well, Jonathan, yes. Thank you so much. I’m gonna go back and, and read some of the PubTrawlr stuff too later today, because I have it all saved on my reading list. So thank you very much and we’ll be inviting you back soon and okay. So PubTrawlr and the Dawn Chorus Group is where people can find you and I’ll put a link, any final parting words of wisdom?

Jonathan: No, thank just thanks so much. I, I love talking about this stuff.

Julia: This is also inspiring.

Gill: Yeah, it was fun Okay. So many great points. We’re gonna…..

Julia: ….send you an email to come back again and talk part two.

Gill: I could keep, keep going, and listening.

Julia: And Gil could talk all day. I’m sure about this implementation Stuff.

Gill: Yeah. I love learning this stuff too

Jonathan: Dito. Right? Thanks so much, guys.

Gill: See you. Bye.