“Barriers & Facilitators” Is a Broken Genre: A Working Hypothesis

There is nothing I find less exciting than an article with barriers and facilitators in the title. Not because implementation is easy. Not because context does not matter. But because, at this point, the genre has become so predictable that the abstract alone often tells you everything you are going to get.

- Leadership.

- Resources.

- Internal support.

- Culture.

- Communication.

I can almost play bingo with it.

These papers often read like they are discovering gravity for the hundredth time. Yes, leadership matters. Yes, resources are uneven. Yes, buy-in is important. None of this is wrong. But very little of it feels additive anymore. The same themes reappear, lightly rephrased, nested under slightly different headings, justified as “context-specific,” and then offered up as fresh insight.

What feels hollow is not the content itself, but the lack of consequence. Barriers-and-facilitators research has become descriptive rather than directive. It tells us what exists but not what matters most, what to tackle first, or what can safely be ignored. Everything is a barrier. Everything is a facilitator. And therefore, nothing is prioritized.

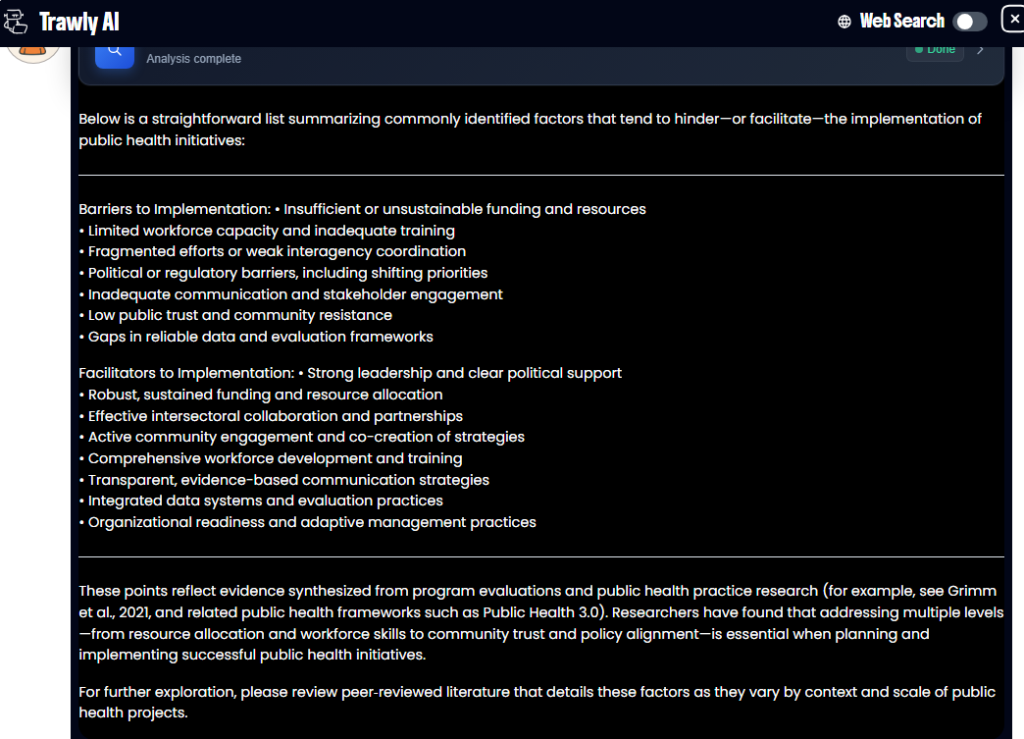

Here, I asked what Trawly thought of this question.

Frameworks like CFIR were supposed to help with this. They gave us a shared language, a way to organize the chaos. But organization is not the same thing as decision-making. We still lack anything resembling a prioritization matrix that helps practitioners answer the question they actually care about: If I can only change one or two things, where should I put my energy?

Surely there is a Pareto principle hiding in this literature. Twenty percent of factors likely drive eighty percent of implementation success or failure. Everett Rogers gestured toward this with diffusion dynamics. John Kotter did the same with change processes. But somewhere along the way, research on barriers and facilitators drifted toward cataloging rather than testing leverage points.

Which is why I suspect the “true barriers” are not the ones most commonly reported. The real constraints are rarely neutral or technical. They are uncomfortable. They live in power, incentives, time, trust, and governance. They are about who benefits from the status quo, who bears the cost of change, and who actually gets to decide. These are harder to measure, publish, and fix. So instead, we talk about “resources” as if budgets appear and disappear by magic, untethered from politics or priorities.

There are now countless syntheses and meta-syntheses of barriers and facilitators. And yet, it feels like we are standing in the same place we were years ago. Replication is essential to science, but repetition without refinement starts to feel like spinning our wheels in the mud. We keep confirming what we already know, without sharpening it into guidance that moves the field forward.

My working hypothesis is simple and a little cynical: barriers and facilitators has become a safe genre. It allows us to gesture at complexity without confronting power. It produces publishable findings without forcing trade-offs. And it rarely demands that we say, out loud, “This matters more than that.”

Until we do that, we will keep producing studies that are technically sound, theoretically aligned, and practically underwhelming. And we will keep pretending that naming the same obstacles, again and again, is the same thing as overcoming them.